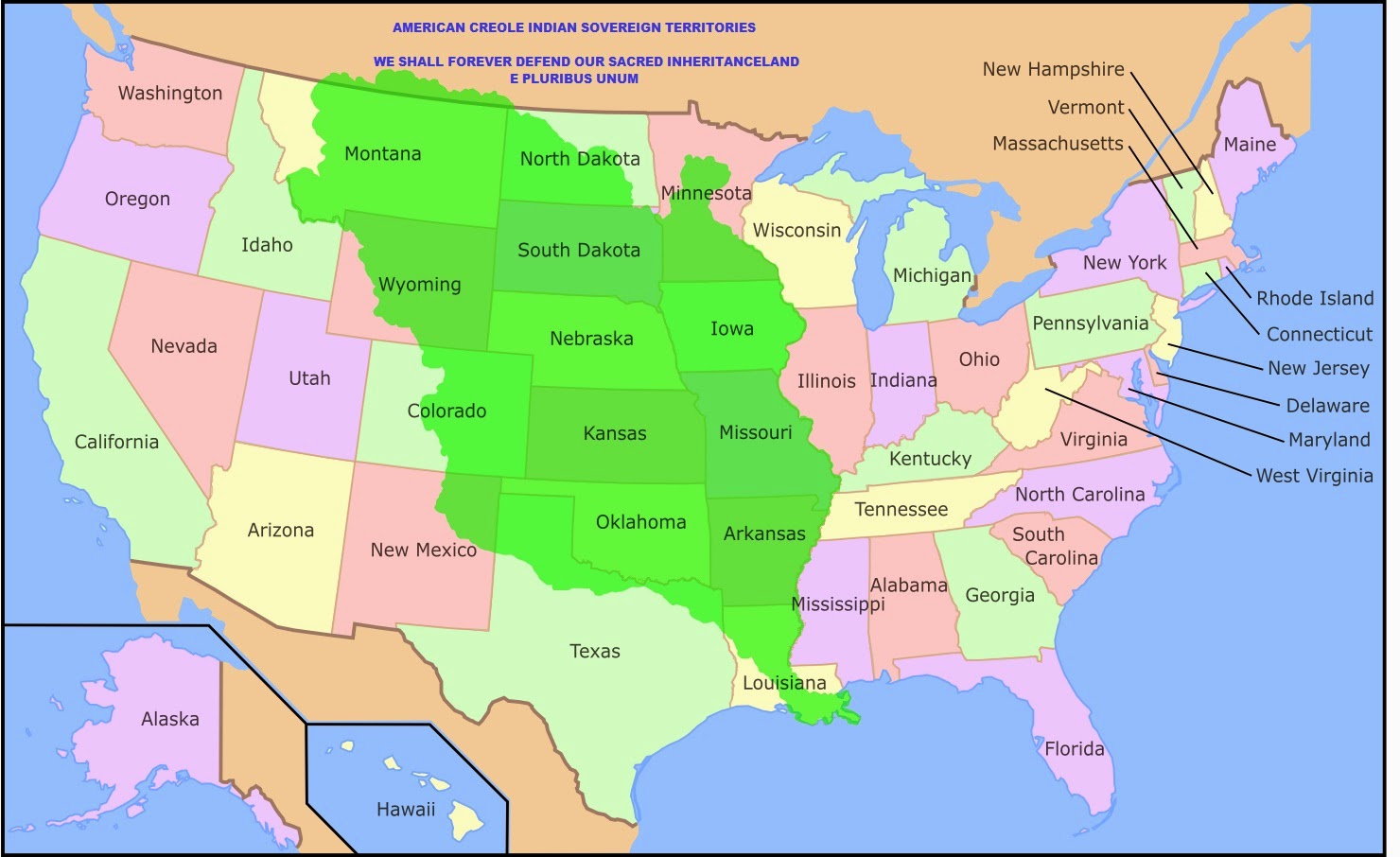

American Creole Indian National History: Ancient West Feliciana Houma-Choctaws

|

American Creole Indian Nationalism:

"The term"tri-racial isolates" is distasteful today, but its existence is part of history that we must recognize....

"As details have fallen together, it has become apparent that the isolate groups are, in fact, remnant Native American communities that have remained outside the official system of recognized tribes." (Ned Heite)

American Creole Indians command INDISPUTABLE aboriginal sovereign rights. We DO NOT abdicate or defer these rights.

The State of Arkansas a Creole Indian Territory of our ancient ancestors; the Ancient Caddo, Choctaw, Houma & others who intermarried with Creoles for survival & destiny, officially acknowledged these indigenous ethnic group rights by way of the Arkansas Department of Education in 2005 after a year-long highly intensive and exhaustive Equity Assistance Center (EAC) investigatory review.

As the Great State of Arkansas has ALREADY done, we, the 1803 Louisiana Purchase Treaty American Creole Indian Nations, unified descendant's of the aboriginal ethnic tribes, bands & clans of our Inheritance-Land, are calling upon the federal government and all state governments to acknowledge their legal obligations under the 1803 Louisiana Purchase Treaty (a bilateral NOT unilateral agreement), and to repair any and all damage for any and all infractions thereof.

"The term"tri-racial isolates" is distasteful today, but its existence is part of history that we must recognize....

"As details have fallen together, it has become apparent that the isolate groups are, in fact, remnant Native American communities that have remained outside the official system of recognized tribes." (Ned Heite)

American Creole Indians command INDISPUTABLE aboriginal sovereign rights. We DO NOT abdicate or defer these rights.

The State of Arkansas a Creole Indian Territory of our ancient ancestors; the Ancient Caddo, Choctaw, Houma & others who intermarried with Creoles for survival & destiny, officially acknowledged these indigenous ethnic group rights by way of the Arkansas Department of Education in 2005 after a year-long highly intensive and exhaustive Equity Assistance Center (EAC) investigatory review.

As the Great State of Arkansas has ALREADY done, we, the 1803 Louisiana Purchase Treaty American Creole Indian Nations, unified descendant's of the aboriginal ethnic tribes, bands & clans of our Inheritance-Land, are calling upon the federal government and all state governments to acknowledge their legal obligations under the 1803 Louisiana Purchase Treaty (a bilateral NOT unilateral agreement), and to repair any and all damage for any and all infractions thereof.

"On

November 30, 1803, according to stipulations in the Louisiana Purchase

Treaty and by formal action, the French rendered the entire Louisiana

Territory an absolutely free country. And it remained that way until

circa 1818, when the legislature of the newly formed state of Louisiana

ruled otherwise.

By

those acts, in deliberate violation of the LPT, Louisiana became just

another Jim Crow State in the Deep South. At the time of the American

takeover of the vast Louisiana Territory, tens of thousands of indigenous people and people

with lineage to Africa were among the inhabitants.

Some

were free, but most were slaves. Nevertheless, neither free or slave

was ever apprised of their treaty rights. Consequently, both the

so-called free people of color and chattel slaves were forced to suffer the

realities of degradation, hostility, and other forms of inequities

brought about by segregation, discrimination, racism and bigotry.

Naturally,

an undercurrent of resentment against the Americans flowed throughout

the Creole community. And that resentment did not begin to abate until

after World War II. Prior to that war, the older Creoles did not refer

to themselves as Americans.They considered it an offense should anyone

else referred to them as Americans. I saw many older Creoles spit on the

ground after mentioning the word "Merican.""

Louisiana Creole Gilbert E. Martin, Creole Treaty Rights

E Pluribus Unum- Out Of Many, ONE

Chief Elder Ean Lee Bordeaux, pro per

The Ancient West Feliciana Parish Houma-Choctaws

D'Choctaw Clan

Bordeaux Band

Our Choctaw ancestors are well-known. Our Ancient West Feliciana Parish Houma ancestors are much less known. We, The Ancient Houma-Choctaw of West Feliciana Parish, stayed put, when most of our fellow clansmen, now called the United Houma Nation (UHN), "went", more like, were driven south.

Many of us intermarried with the Creole & Redbone planters that protected and maintained Houma and Choctaw interests and cultures and shared we our fates together. We refused to allow our unique Creole-Tribal cultures to be assimilated, no matter the threat, no matter how small our remnant bands became.

HISTORY

Most researchers universally accept the early history of the Houma (1682-circa 1765). The tribe enters the historical record in the journal of LaSalle in 1682 when the explorer notes that he passed their village but does not visit them. They were visited by Tonti in 1686 and D’Iberville in 1699 beginning a friendship with the French that continues to this day.

In 1706 the Houma left their village, located at the site of the modern-day Angola Penitentiary, and began a southward migration that brought them to the area of the LaFourche Post in the mid-1700’s. Conflict arises when we attempt to connect these historic Houma with the United Houma Nation of today. Indeed the gist of the Bureau of Indian Affairs decision to not Federally Recognize the UHN is tied to this one point. In the opinion of this bureaucracy the tribe can not make this all-important historic tie-in. Presented here in this chapter is a simple presentation of facts that I feel were overlooked. They show a clear link between the United Houma Nation and the historic Houma Tribe.

In 1793, Judice ( 3 June 1793 PPC ) reports a Houma population that remained relatively stable over the preceding ten years;

“All the body of this ( Houma ) Nation forms no more than ninety persons.

15 in a village at Cantrelle’s

17 in a village at Verret’s

58 in a village at Judice’s

( 13 men, 22 women, 23 children )

15 in a village at Cantrelle’s

17 in a village at Verret’s

58 in a village at Judice’s

( 13 men, 22 women, 23 children )

whose places were all located near the confluence of Bayou LaFourche an the Mississippi River at Donaldsonville.”

Just downriver from the LaFourche at Cabahanoce ( St. James ), situated side by side, were the resident plantations of Judice, Cantrelle and Verret. In the forested backlands of these landholdings were the three Houma villages listed by Judice. These settlements had existed at least since 1783, corresponding with the end of Galvez’s campaigns against the British.

These types of settlements and their relationship to the colonial plantation system are well documented.

“By the nineteenth century….they moved to isolated areas-swamps and pinewoods-not in demand by the expanding plantation economy of the time. Planters used Indian hunters to augment their meat supplies, to track down runaway slaves and to provide entertainment. Stickball games and even traditional dances were held on the plantations to amuse the planter’s guest….The bands of Choctaw and other Indians were permitted to live in the back-swamps or in hill areas of plantations. Creole planters became patrons of these groups and frequently attempted to protect them from Anglo-American intruders.”( The Historic Indian Tribes of Louisiana, Kniffen, Gregory and Stokes 1987 )

“By the nineteenth century….they moved to isolated areas-swamps and pinewoods-not in demand by the expanding plantation economy of the time. Planters used Indian hunters to augment their meat supplies, to track down runaway slaves and to provide entertainment. Stickball games and even traditional dances were held on the plantations to amuse the planter’s guest….The bands of Choctaw and other Indians were permitted to live in the back-swamps or in hill areas of plantations. Creole planters became patrons of these groups and frequently attempted to protect them from Anglo-American intruders.”( The Historic Indian Tribes of Louisiana, Kniffen, Gregory and Stokes 1987 )

By tracking the Houma references in the PPC and correlating the leaders most associated with the different planters ( Judice, Cantrelle and Verret ) I believe we get a clear picture of which tribal leader lead which band.

The 15 at Cantrelle’s were lead by Mico-Houma or Chac-Chouma, at Judice’s was the remnant of Calabe’s band, numbering 58, now lead by Mingo Oujo, while at Verret’s was the band of 17 lead by Natiabe. It is this band at Verret’s that would become the ancestors of the UHN.

With Nicolas Verret and the PPC reference to a Houma village on his plantation comes a firm historic link. Nicolas Verret had a liaison with a woman named Marianne ( parentage unknown ), a free woman of color. From this union two sons are born, Zenon and Paulin Verret. These two eventually marry into the UHN ancestral community and have extensive documented relationships with known UHN ancestors. It is not, therefore, unreasonable to assume that Marianne, her sons and the UHN ancestors were all part of the Houma settlement at Verret’s in 1793.

The Houma village on Bayou Cane, called Whiskey Point by the local settlers [ a corruption of Ouisky the Houma word for cane ] was initially established as a seasonal settlement, probably while they were still at Verrets.

“From all indications, Indians moved freely from plantation to plantation to hunt and possibly raise crops for themselves and their patrons.” ( Bill Starna 1996 )

It is important to note that Verret had a large land grant on Bayou Terrebonne that encompassed the Bayou Cane area. Bayou Terrebonne and the surrounding area at this time was a vast wilderness virtually uninhabited by any save the Indians.

“….Finally, few Acadians dared to explore, and only seven families actually occupied lands in the densely forested, natural levee along Bayou Terrebonne.” (The Founding of New Acadia, Carl Brassaux, 1987)

The early church records of the UHN ancestral community such as the 1808 marriage of Jacques Billiot and Rosalie Courteau and the 1809 marriage of Michel Dardar and Adelaide Billiot were witnessed by landowners from upper Bayou Terrebonne such as Thibodaux and Malbough. It is the Bayou Cane village and the Indians that lived there that became the namesake of the town founded in 1834.

“Court, in the early days of the Parish, was held in a little building on Bayou Cane. On May 10th, 1834, Richard H. Grange and Hubert M. Belanger donated to the Parish of Terrebonne the property on which the present Courthouse and other public buildings are situated. This land was valued at the time at $ 150. The land on each side of this was laid off into town lots and the town of Houma came into existence, bearing the name of the Indian tribe that lived and loved and worshipped among its groves, the ancient Houmas, which means the sun….” (Directory of the Parish of Terrebonne, E.C.Wurzlow, 1897)

Also of note are the oral histories of the tribe that tell of the Houma Courthouse being built on Rosalie Courteau’s land. The misunderstanding has been that it was not the modern courthouse but rather the original one on Bayou Cane. Sometime after the American takeover in 1803 the Houma tribe filed a claim to twelve sections of land, 7680 acres, on Bayou Black/Boeuf.

“The Houma tribe of Indians claims a tract of land lying on Bayou Boeuf or Bayou Black, containing twelve sections. We know of no law of the United States by which a tribe of Indians have a right to claim land as a donation.” ( ASP 1834 3:265, 1817 )

“The Houma tribe of Indians claims a tract of land lying on Bayou Boeuf or Bayou Black, containing twelve sections. We know of no law of the United States by which a tribe of Indians have a right to claim land as a donation.” ( ASP 1834 3:265, 1817 )

This appears to be an attempt by the Houma to secure a land base in the face of a growing White population. Likely, they hoped the American Government would honor the Louisiana Purchase Agreement in which they promised to continue the Louisiana Colonial land policies that respected, for the most part, tribal landclaims.

Unfortunately the claim was rejected but it stands as evidence of a Houma presence in the area during this period. At this time Bayou Black ( called Bayou Boeuf on its western end ) flowed from the swamplands northwest of the town of Houma. The bayou cut through the backlands of the tribes Bayou Cane settlement, hence it would be logical to assume that the tribe at Bayou Cane and the tribe that filed the landclaim where one in the same.

It is the contention of the BIA’s Branch of Acknowledgement and Research that the ancestors of the UHN were not a tribe at the beginning of the nineteenth century but rather a few Indian individuals who married into the surrounding population and eventually produced a separate community. [a so-called tri-racial isolate or island]

This theory is clearly contradicted by the following chart (1) of baptisms. The initial perception has been that they took place within a white community but a closer examination of the dates ( Monday July 7th, and Tuesday July 8th, 1817 and Wednesday Dec. 16th, and Thursday Dec. 17th, 1818 ) reveal these to be mid-week services taking place within the UHN community.

The White sponsors of the baptisms were, for the most part, a single extended family that lived near the Houma’s lower bayou settlement.It may have been in there house that the actual service was held, the nature of the service was describe a couple generations later.

“I went to visit all those families who cannot come to church. These visits took me two weeks…to see those who are in the islands neighboring Bayou Terrebonne. The people are not able to come to church. I go from time to time among them for baptisms and communions. These are practically all decent well-disposed Indians. I have already given communion to a good many of them. When I arrive among these people they gather ( from ) all the islands to attend Mass. I stay in the house most suitable. One sees that the sight of a priest makes them happy and it is with sorrow that they see me leave them. The day of departure ( having ) come, they take great pleasure in taking me to the embarkation”. ( Fr. Dene’ce to Monsignor, 10 Dec., 1868 )

With these records we see a single Houma community in the early nineteenth century, with no distinction between Billiot, Courteau or Verdin. As the community continues we see it again in 1836 ( chart 2 ) as the tribe attempts to secure another land base, this time in the wilderness west of Pointe Coupee near the town of Fordoce. Perhaps it was the efforts of the American Government at the time to remove tribes to the Indian Territory that persuaded the Houma to abandon this area but it does serve to show the continuation of a Houma community.

Lastly, we consider the history of Abbe Rouquette and the St. Tammany Choctaw. Father Rouquette was a missionary to the Choctaw community centered around Bayou LaCombe in the mid to late 1800’s. Twice in the text is mention of the Indians of Barataria who are invited to the annual Feast of the Dead and are also invited to the funeral of Abbe Rouquette in 1887. At this time the ancestors of the UHN are known to inhabit the Barataria area.

By tying these scattered documents and references into a single narrative we see a single Houma community from 1783 on into the late nineteenth century. A community that links directly to the modern United Houma Nation.

This clearly contradicts the Branch’s assertion that the Houma of Bayou Terrebonne between 1809 and 1820 “….did not live in a distinct, identifiable Indian community-geographically, socially or politically.”

And it shows that their decision to not recognize the UHN was based on bias and ignorance.

History (Timeline)

1682 Lasalle notes existence of Houma tribe at intersection of Mississippi River and Red River.

1685 Tonti records first European-Houma contact

1699 Houma tribe visited by Iberville

1706 Large numbers of Houmas perish in Tunica massacre. Segment of Houma tribe moves south from Angola area.

1718 Houmas negotiate peace between Chitimacha and the French.

1718 Houmas negotiate peace between Chitimacha and the French.

1723 Tunica and Natchez tribes seek peace with the Houmas.

1763 Peace Treaty of Parish places Houmas hunting grounds under control of the English and villages in Spanish territory.

1765 Houma and Alabama warriors raid the British fort Bute, at Manchac, during the waning days of the Pontiac rebellion.

1766 Houma tribe moves south from Donaldsonville.

1774 Mississippi east bank Houma village is sold to Conway and Latil.

1800 Houmas begin to move to present location in Terrebonne and Lafourche Parish.

1803 U.S. buys large tract of land from France: the Louisiana Purchase Daniel Clark reports only 60 Houmas remaining above New Orleans.

1806 John Sibley reports to the U.S. Secretary of State that Houmas “scarcely exist as a nation.”

1811 Author H.M. Brackenridge writes that Houmas “extinct”.

Houma Chiefs (including Louis Savage) meet with W.C.C. Claiborne, governor of the Louisiana Territory, to formalize relations with the United States.

Houma Chiefs (including Louis Savage) meet with W.C.C. Claiborne, governor of the Louisiana Territory, to formalize relations with the United States.

1814 Houma tribe files land claim with U.S. government.

1821 John J. Audubon mentions presence of Houmas in Southern Louisiana.

1832 The death of Louis Savage, famous Houma Chief and maternal uncle of Rosalie Courteaux.

1834 The town of Houma, Louisiana is founded, named after the Houma Indian village in the vicinity.

1840 The Houmas southern migration was at an end.

1859 Rosalie Courteaux purchases “large amount” of land for Houma tribe.

1870-80’s Houma spread west from Lafourche Parish and Terrebonne Parish to St. Mary Parish.

1883 The death of Rosalie Courteaux heroine and matriarch of the Houma People.

The seven principal Houma settlements at the beginning of the twentieth century were: DuLarge, Dulac, Montegut, Point Barre, Point au Chene, Isle de jean Charles, Grand Bois and Golden Meadow.

The seven principal Houma settlements at the beginning of the twentieth century were: DuLarge, Dulac, Montegut, Point Barre, Point au Chene, Isle de jean Charles, Grand Bois and Golden Meadow.

1907 John Swanton “re-discovers” the Houmas.

1918 Henry Billiot loses his court challenge to enter his children in public school. This was the first, recorded, formal assault by the tribe on the Terrebonne parish School System.

1920 Houma tribe begins to seek federal recognition.

1931-40 Houma tribe contacted and “studied” by Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) officials and anthropologist Nash, Underhill, Meyer, and Speck.

1932 Protestant education mission schools open for Indian students in Terrebonne at Dulac, DuLarge, and Pointe-aux-Chene.

1935 The dedication service for Clanton Chapel in Dulac, “the only Indian church in Louisiana” at the time.

1940-48 Parochial and public elementary schools open for Indian students in Terrebonne Parish

Late 1950’s Houmas are allowed to attend Indian schools up to the seventh grade.

Late 1950’s Houmas are allowed to attend Indian schools up to the seventh grade.

1960 Stoutenburgh lists Houmas as “extinct”.

1963 Houma children admitted to public schools.

1963 Frank Naquin, the community leader in Golden Meadow, sends Helen Gindrat and Delores Terrebonne to the American Indian conference in Chicago. This event would become the catalyst for the modern political movements in the Houma community.

1972 Houma Tribes, Inc. is established at Golden Meadow in Lafourche Parish.

1974 Houma Alliance, Inc. is established at Dulac in Terrebonne Parish. First Title V Indian Education program is funded in Lafourche & Terrebonne parish.

1975 Houma tribe joins with other Indian tribes of Louisiana to form the Inter-tribal Council.

1975 – present United Houma Nation administers grants & job training programs in association with Inter-tribal Council.

1979 First formal meeting of the United Houma nation Tribal council after the merger of the Houma Tribe and the Houma Alliance.

1985 United Houma Nation files petition for federal recognition.

1986 United Houma Nation under the leadership of Chairman Kirby Verret and Vice-Chairwoman Helen Gindrat

1990 Tribal roll books closed. Only newborns can be registered.

1991 BIA places United Houma Nation on active status.

1992 Laura Billiot elected Chairwoman of United Houma Nation.

1993 Tribal enrollment numbers 17,000.

1994 United Houma Nation receives negative proposed findings.

1996 United Houma Nation files rebuttal to negative proposed findings.

1997- 2011 United Houma Nation under the leadership of Brenda Dardar Robichaux, Chairwoman and Michael Dardar, Vice-Chairman.

1999 The Houma Tribal Council meets with a delegation of French Senators. Principal chief Brenda Dardar Robichaux is presented with a medal from the French Government, becoming the first “Medal Chief” since the colonial period.

1996-present United Houma Nation awaits its final determination from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

June 19, 2011 Thomas Dardar Jr. sworn in as new principal chief of the United Houma Nation. He takes over from Brenda Dardar Robichaux after 13 years.

May 22, 2014 HARTFORD, Conn. — The U.S. Interior Department announced proposed changes to the rules for granting federal recognition to American Indian tribes, revisions that could make it easier for some groups to achieve status that brings increased benefits as well as opportunities for commercial development.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs said it overhauled the rules to make tribal acknowledgment more transparent and efficient.

The changes include a requirement that tribes demonstrate political authority since 1934, where they previously had to show continuity from “historical times.” That change was first proposed in an earlier draft and stirred criticism that the standards for recognition were being watered down.

Kevin Washburn, an assistant secretary with Indian Affairs, said the rules are no less rigorous. He said 1934 was chosen as a dividing line because that was the year Congress accepted the existence of tribes as political entities.

“The proposed rule would slightly modify criteria to make it more consistent with the way we’ve been applying the criteria in the past,” Washburn said in an interview.

Gerald Gray, chairman of Montana’s Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians, said the change offers the path to recognition that his people have sought for decades.

The landless tribe of about 4,500 members has been recognized by Montana since 2000, but its bid for federal recognition was rejected in 2009 partly because the tribe could not document continuity through the early part of the 20th century. Gray said the denial illustrated how the process is broken.

“For a lot of the Plains tribes, and Indians in the country as a whole, there’s oral history but not a lot of written history,” Gray said. “But we can prove our existence as a tribal entity and having a tribal government back to [1934].”

The newly published rules represent the first overhaul in two decades for a recognition process that has been criticized as slow, inconsistent and overly susceptible to political influence. The Interior Department held consultations on the draft proposal across the country in the summer of 2013 accepted comment for at least 60 days before the rules were to be finalized.

Comments

Post a Comment

You are welcome to email your tips, corrections and/or comments to: aidcommission@gmail.com please indicate if you wish to remain anonymous or otherwise. We will post your comment without edit.